Satellites for Minor Planets

05 August — 26 August 2017

05 August — 26 August 2017

Solo exhibit — Blanc Gallery

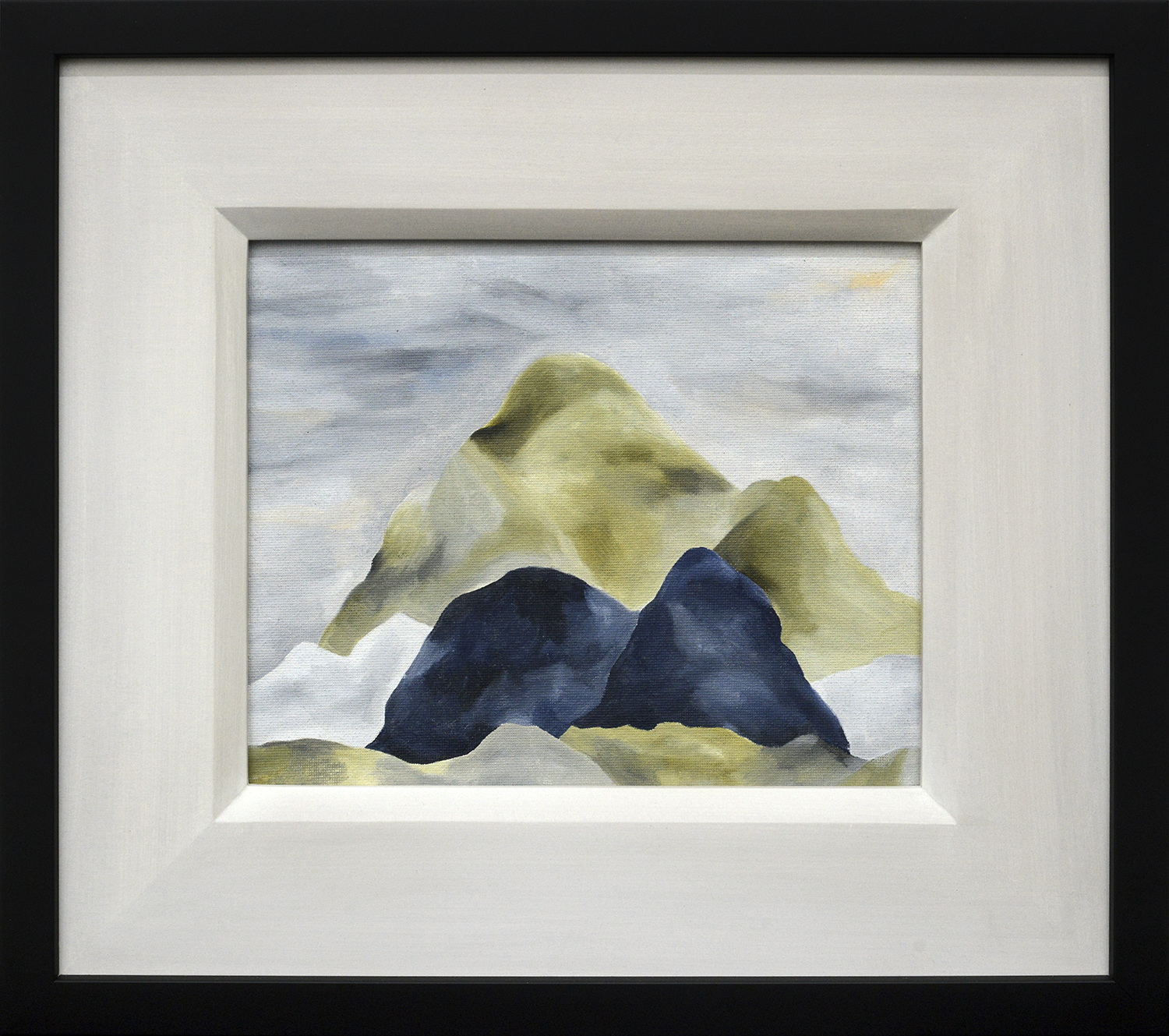

The Center of the World: B

watercolour on paper

2017

watercolour on paper

2017

Can you understand being alone so long

you would go out in the middle of the night

and put a bucket into the well

so you could feel something down there

tug at the other end of the rope?

”The Abandoned Valley”

Jack Gilbert

Fragmentation I—VIII

2017

oil on canvas

8 in. x 10 in.

“Sputnik 1” was the first artificial Earth satellite, launched by Soviet Union in 1957. It orbited the Earth 1,440 times before burning up as it descended into the atmosphere. Since then, other satellites have been launched, intended, among other things, to gather and disseminate all sorts of information about the places they orbit.

The first part of a series of shows, Satellites for Minor Planets examines landscapes and geography in a way that considers them portraits or markers of the self. What can be learned from information gathered from an observable distance? What can phenomenological details say about where you are? What can be learned about someone, through the spaces

they inhabit?

Although devoid of obvious signs of life, the paintings in the show are small captures, portraits, made or relayed by an observer from a distance, a way to get to know a place, or a person, but never quite getting near it.

The word “satellite” was first used by Johannes Kepler in 1610 and is derived from Latin, satelles, which means “guard,” “attendant,” or “companion,” rendering natural satellites almost like sentient beings that accompany their primary planets or minor planets as they complete their orbit around the sun. Like the Earth’s own moon, natural satellites are a semi-permanent fixture that goes around them, pulled in by the strength of their gravity, which is also what keeps a full collision from happening.

It’s almost Sisyphean, the satellite’s full-fledged devotion to a small, perhaps inconsequential thing, destined to orbit their companions until they go up in flames, even moreso when the object of interest is a minor planet—asteroids and dwarf planets, among others.

But what then is the point of these pointless revolutions? In And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos, John Berger writes of the moment existence is made possible because of light: “Then it could be said: The visible exists because it had already been seen.”

The satellite’s relentless orbiting feels like a relentless pursuit of proof. These journeys around objects that are perpetually kept at a distance feel lonely but are in some ways necessary. There must be something out there that deserves to be seen, and so, to exist.

The first part of a series of shows, Satellites for Minor Planets examines landscapes and geography in a way that considers them portraits or markers of the self. What can be learned from information gathered from an observable distance? What can phenomenological details say about where you are? What can be learned about someone, through the spaces

they inhabit?

Although devoid of obvious signs of life, the paintings in the show are small captures, portraits, made or relayed by an observer from a distance, a way to get to know a place, or a person, but never quite getting near it.

The word “satellite” was first used by Johannes Kepler in 1610 and is derived from Latin, satelles, which means “guard,” “attendant,” or “companion,” rendering natural satellites almost like sentient beings that accompany their primary planets or minor planets as they complete their orbit around the sun. Like the Earth’s own moon, natural satellites are a semi-permanent fixture that goes around them, pulled in by the strength of their gravity, which is also what keeps a full collision from happening.

It’s almost Sisyphean, the satellite’s full-fledged devotion to a small, perhaps inconsequential thing, destined to orbit their companions until they go up in flames, even moreso when the object of interest is a minor planet—asteroids and dwarf planets, among others.

But what then is the point of these pointless revolutions? In And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos, John Berger writes of the moment existence is made possible because of light: “Then it could be said: The visible exists because it had already been seen.”

The satellite’s relentless orbiting feels like a relentless pursuit of proof. These journeys around objects that are perpetually kept at a distance feel lonely but are in some ways necessary. There must be something out there that deserves to be seen, and so, to exist.

Imagined Constructions I—XVI

oil on canvas

8 in. x 10 in.

2017

Like errant homeless ghosts

oil on canvas

8 in x 10 in

2017

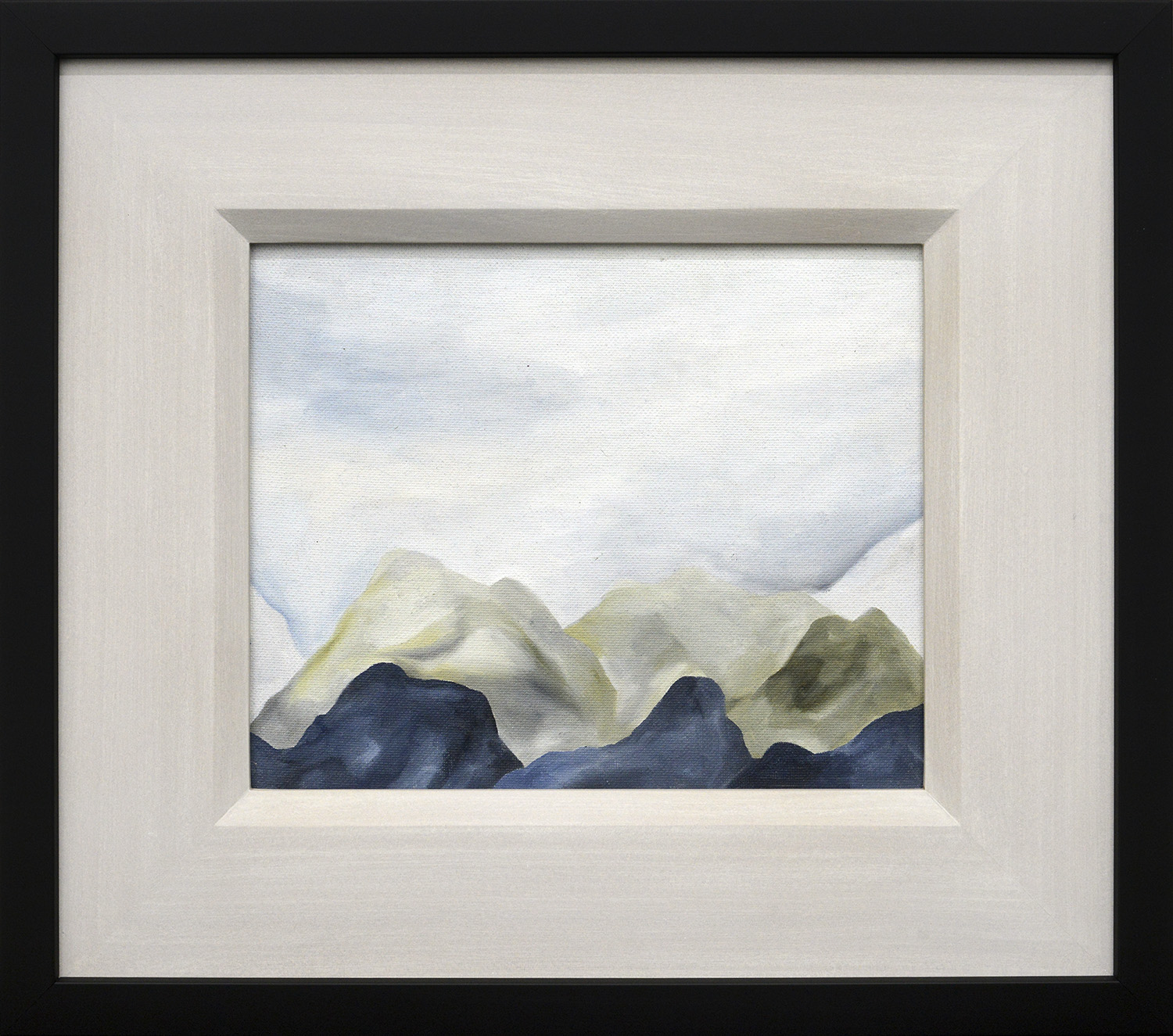

The Center of the World: A

watercolour on paper

2017